The fringe belt concept is one of the oldest concepts in the field of urban morphology. While urban morphology schools had not yet taken shape in an organizational form, the concept of the fringe belt was used by Herbert Louis in 1936, and the fringe belts of Berlin were introduced. A quarter of a century later, Conzen (1960) described the fringe belts of Alnwick. It took its place as a concept within the historico-geographical approach, which was later called the Conzen school of morphology and is also one of the approaches to urban morphology. It continues to attract attention as one of the most studied topics in the field of urban morphology.

At its most basic, the urban fringe belt theory is based on the uneven nature of urban growth over time in response to business cycles and the prediction of an alternative land use belt in the outward growth of cities with a distinctly different character produced by these fluctuations. In good economic times, private capital is readily available, and therefore residential developments constitute a large part of the extensive and new urban environment.

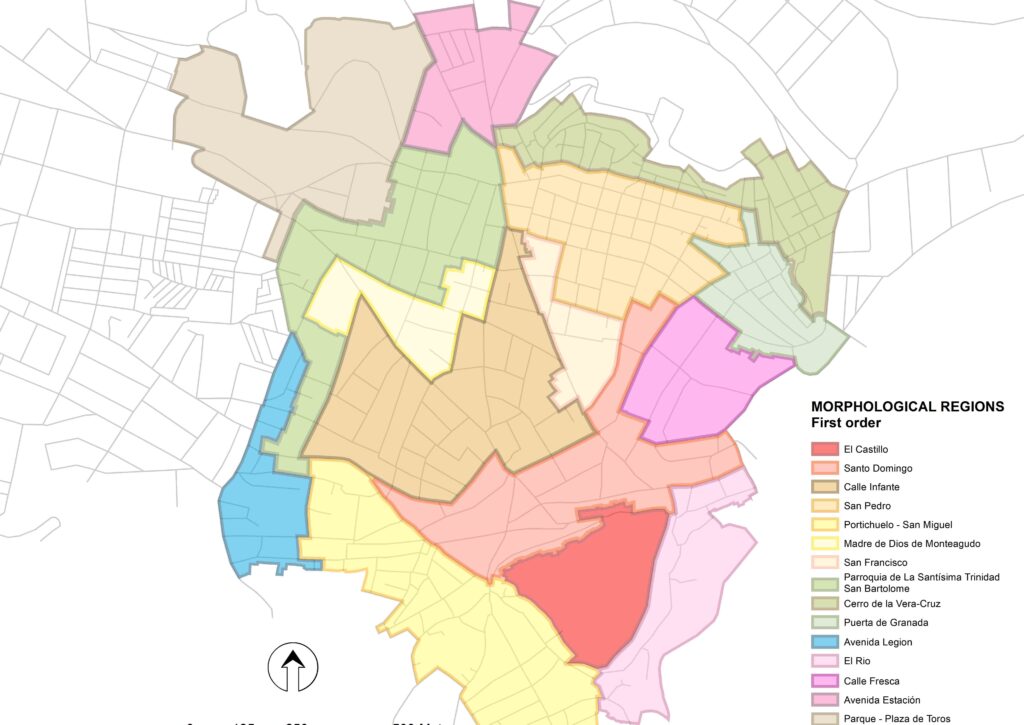

During economic downturns, private capital is scarce, but public capital remains more accessible, and as a result many institutional developments (including infrastructure improvements), especially those requiring expensive plots, have the opportunity to accumulate on the urban fringe. During these downturns, private developments seeking or requiring large areas of land also tend to take advantage of low land prices. Typically, such land uses may include cemeteries, parks, villas, military barracks, college grounds, hospitals, golf courses, waste disposal facilities, sports arenas, and religious facilities. The result is a fringe belt of mixed land uses that is less dense and more open in character than the relatively homogeneous residential densities of the previous area (Conzen, 1960). The central conditions for the emergence of fringe belts are (1) a clear sequence of economic cycles that divide urban growth into distinct phases of strong and weak lateral expansion, most marked since the historical rise of industrial capital (Vance, 1971); (2) an established urban core with outward expansion occurring in zones that are in principle similar to the growth rings of trees. When the rate of urban growth does not exhibit a clear pulse, fringe belts are much less likely to form. Similarly, in the absence of a single core around which growth radiates outward, land uses that would normally cluster in fringe belts will appear much more dispersed and less organized in the fringe belts. Old and new cities can develop fringe belts. Historical cities may exhibit up to three successive fringe belts (inner fringe belt, middle fringe belt, outer fringe belt), while younger cities may exhibit only one or two. The middle fringe belt of an older city may be of similar age to the inner fringe belt or middle fringe belt of a younger city. Fringe belts develop an internal history as they develop over time. They pass through two major phases, which for analytical purposes are divided into phases of formation and modification, and which may well overlap in chronology. During the formation phase, they typically progress from an early fixation phase (usually connected to a strong anchorage line) to an expansion phase and then to a consolidation phase.

Fringe belts play an important role in determining conservation priorities and managing the urban landscape, guiding urban planning practices and transferring historical heritage to the future (Conzen, 1966; Whitehand, 1988; Buswell, 1980).

The importance and application areas of fringe belt areas can be grouped as follows:

i. Understanding the historical-geographical development of cities

ii. Understanding the natural and cultural characteristics of cities and whether they should be regulated in light of broader social values

iii. Provides data for design and redesign at lower densities, design in more complex environments, and preservation of their character

iv. Urban growth management

v. Provides a powerful way of understanding the physical form of urban areas and the process of urban outward growth and internal change

vi. Examining changes in fringe belts highlights important issues of urban transformation that are relevant to planning and design policies for urban management

vii. Helping to reconstruct and clarify the specific processes through which urban areas acquire their physical-cultural character, providing an effective method for localizing these processes in urban space and defining and delimiting character areas based on them

viii. Providing a reference framework for describing, explaining and comparing the physical structure and historical development of urban landscapes

ix. Being an important guide in determining conservation priorities and managing urban landscapes, guiding urban planning practices and transferring historical heritage to the future

References

- Buswell, R. J. (1980). Changing approaches to urban conservation: a case study of Newcastle upon Tyne. Newcastle upon Tyne Polytechnic, School of Geography and Environmental Studies.

- Conzen, M. R. G. (1960). Alnwick, Northumberland: a study in town-plan analysis. Transactions and Papers (Institute of British Geographers), 27, iii-122.

- Conzen, M. R. G. (1966). Historical townscapes in Britain: a problem in applied geography. In J. W. R. Whitehand (Ed.), The Urban Landscape: Historical development and management, Papers by M.R.G. Conzen: Institute of British Geographers, Special Publication, No.13.

- Louis H (1936) Die geographische Gliederung von Gross-Berlin. Engelhorn, Stuttgart, pp 146–171

- Vance, J. E. (1971). Land assignment in the precapitalist, capitalist, and postcapitalist city, Economic Geography 47, 101-20.

- Whitehand, J. W. R. (1988). Urban fringe belts: development of an idea. Planning perspectives, 3(1), 47-58.